The Essential Reading List for 2025

By Corinne Kennedy

Dokusho no Aki - 読書の秋, or “Autumn, The Season for Reading” is a common saying in Japan, and it’s a popular time of the year for all kinds of themed reading lists to be published. As the days grow colder and the nights get longer here in Seattle, books are a welcome companion. For your fall enrichment, Corinne Kennedy has compiled an eclectic list of 12 titles, including fiction and non-fiction books for children, teens and adults.

A Japanese maple in the teahouse garden displays brilliant fall color—Acer palmatum ‘Osakazuki akame’. (photo: Aleks Monk)

I continue to be amazed and inspired by the wonderful selection of children’s books at the Elisabeth C. Miller Library, where I volunteer. And I’m indebted to librarian Laura Blumhagen’s recommendations of relevant books, including some not in the Miller Library’s collection. Like my “Essential Reading Lists” for 2022 through 2024, this year’s article includes titles for children and teens as well as adults.

Listed here are 12 works, two translated from the original Japanese. Five are children’s picture books (three with themes related to the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II), three are fiction and non-fiction works for older children and teens (a contemporary Japanese novel, a book about writing haiku poetry, and a book about our country’s history of anti-Asian racism), and four are fiction and non-fiction books for adults and mature teens. Included in the latter: a Japanese mystery novel published in 1959, a book on haiku that includes poems written by Japan’s most renowned haiku masters and by seven of its lesser-known haiku poets, a memoir of a Nisei teenager’s World War II incarceration, and a book about Japanese garden design and aesthetics. Most of this year’s books are available at local public libraries; three are also available at the Miller Library (as noted by ***).

I believe that as Americans we should be aware of our history and always stand up for our Constitutional rights, which is why this year's reading list includes five books with content about the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans—both first-generation immigrants (Issei) and their second-generation children (Nisei), who were American citizens.

Pink fruits of Hamilton’s spindle tree (Euonymus hamiltonianus), planted north of the Garden’s original gate. (photo: Aleks Monk)

BOOKS FOR YOUNG CHILDREN:

Baseball Saved Us, written by Ken Mochizuki and illustrated by Dom Lee (1993; ages 4-up).

Ken Mochizuki (1954-2025) was a pioneering Japanese American author, journalist, educator, social activist, and actor who grew up in Seattle’s Beacon Hill neighborhood. He died recently, on September 20th. To acknowledge the importance of his life and writings, I’ve added Mochizuki’s picture book to this reading list, even though no copies are currently available at the Seattle Public Library. I’m glad to see the interest shown by so many holds on it, and have relied on online reviews for the following description:

Published in 1993, Baseball Saved Us was an important introduction for young children to the history of the U.S. government’s World War II incarceration camps. After Japan’s 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, Shorty and his family, along with about 120,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast, are sent to a desert camp. But despite having lost nearly everything, the incarcerees begin to build what they can to make their lives more bearable, including a baseball field. Playing baseball, and eventually hitting a championship home run, the young narrator begins to regain a sense of dignity and self-worth. The muted browns and golds of the artist’s illustrations convey the bleakness of camp life—armed guards, cramped barracks without privacy, dust storms, and dehumanizing racism.

Every Peach is a Story, written by David Mas Masumoto and Nikiko Masumoto, and illustrated by Lauren Tamaki (2025; ages 4-8).***

This charming picture book by authors and organic farmers David Mas Masumoto and his daughter Nikiko Masumoto is the story of young Midori, her family, and their peach farm. One spring, young Midori asks Jiichan, her grandfather, whether the peaches are ripe—and then she bites into a very hard peach. Jiichan reassures her that “You’ll know it’s ready when it tastes like a story…. a peach, like a story, needs time to grow.”

Throughout the book, Midori’s grandfather and father teach her about her Japanese American heritage—her ancestors’ arrival in America and their patience, persistence, hard work, and bittersweet survival. Learning to pay attention to the changing seasons and the farm’s peaches, Midori also discovers how her family has grown roots and developed their deep connection to the land.

Listening to Trees: George Nakashima, Woodworker, written by Holly Thompson and illustrated by Toshiki Nakamura (2024; ages 4-8).***

This beautifully written and illustrated picture book is a brief biography for children of the life and work of eminent Nisei woodworking artist George Nakashima (1905-1990). Born in Spokane, he earned degrees in architecture from the University of Washington and MIT. During the 1930s, he worked in France, Japan and India, then returned to the U.S. and decided to leave behind architecture for a vocation crafting fine wood furniture. But in 1942 he and his family were incarcerated at Minidoka prison camp. Despite losing everything and the hardships of the camp, Nakashima was fortunate to learn the art of traditional Japanese woodworking from an Issei carpenter also incarcerated there. After their release from camp, the family settled in Pennsylvania, where they built a home and workshop. As described in the book:

“George had logs carefully sawn. When the wood dried, he studied each slab for contour and grain. Then he began woodworking—marking, cutting, carving, notching, joining, and finishing—aiming to capture the spirit of the tree.”

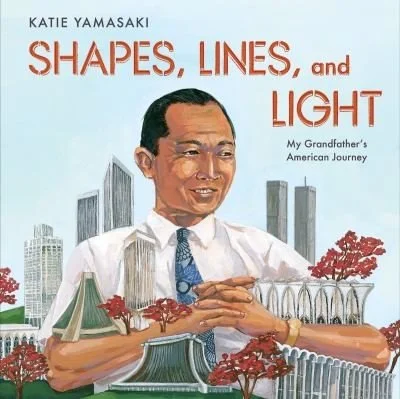

Shapes, Lines and Light: My Grandfather’s American Journey, written and illustrated by Katie Yamasaki (2022; ages 6-8).

This picture book by author and artist Katie Yamasaki celebrates the life of her grandfather, renowned Japanese American architect Minoru “Yama” Yamasaki (1912-1986). In his light-filled buildings, including the U.S. Science Pavillion built for the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair (now known as the Pacific Science Center), he sought to evoke feelings of "serenity, surprise, and delight."

Shapes, Lines and Light reveals Yama’s childhood in Seattle's Japanese American community, his long hours of grueling labor in Alaskan salmon canneries, his success as architectural student, and the unique beauty of “the transformative structures he imagined and built”—in the U.S., Asia, and the Middle East. But as a Nisei, he experienced unrelenting anti-Asian racism and discrimination before, during and after World War II, and was always seen as an outsider by the architectural establishment.

“This striking picture book renders one artist's work through the eyes of another, and tells a story of a man whose vision, hard work, and humanity led him to the pinnacle of his field.” (all quotations are from the book’s jacket)

Shell Song: Based on a True Family Story, written and illustrated by Sharon Fujimoto-Johnson (2025; ages 4-8).

With evocative writing and lovely illustrations, Fujimoto-Johnson tells the story of her grandfather, Shigeki Fujimoto, who lived with his wife and children in Hawai’i and was arrested by the FBI after Japan’s 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor. A U.S. citizen, community leader, and vice president of a business that imported household goods from Japan, he was classified as an “alien enemy,” accused of being a spy for Japan, and incarcerated without trial. Because Japanese Americans made up more than 35 percent of the Hawaiian population, most were not incarcerated. Nonetheless, martial law was declared and their civil rights restricted.

Fujimoto-Johnson writes lovingly of her grandfather, who died long before she was born—and his love of music, seashells and the sound of the ocean. Even while incarcerated, he collected shells, which he brought home and passed on to his children and grandchildren. The author’s historical epilogue ends as follows:

“And yet, I believe our most precious inheritance is story, passed down generation to generation, like tiny glistening shells. I can only imagine what my grandfather must have felt as he collected these shells day after day, torn from his family, confined behind barbed wire, and powerless against the oppression of his own country. My hope is that these shells carried for him not just reminders of time and loss but also tiny glimmers of of hope against the fragility of liberty and justice for all.”

Tea oil camellia (Camellia oleifera), planted just south of the Garden’s original gate. (photo: Corinne Kennedy)

FICTION & NON-FICTION FOR OLDER CHILDREN AND TEENS:

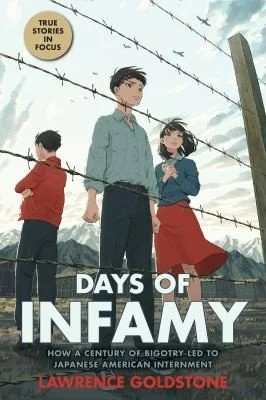

Days of Infamy: How a Century of Bigotry Led to Japanese American Internment, by Lawrence Goldstone (2022; ages 12-18).

Lawrence Goldstone, a Constitutional law scholar known for his books on racial injustice and the civil rights movement in the American South, adds to our understanding of the Japanese American incarceration in World War II with this history of the racial prejudice and discrimination that preceded it. Unfortunately, this history is not well known. From Kirkus Reviews:

“Goldstone describes discussions of race at the time the Constitution was written, traces mid-19th-century Japan--U.S. relations, and shows the rising vitriol following the later arrival of Japanese laborers in America. The narrative describes campaigns by White supremacists, particularly in the American West, to limit access to immigration, birthright citizenship, union membership, property ownership, and naturalization and to generate a frenzy of anti-Asian hatred.”

Goldstone shows how President Roosevelt’s 1942 Executive Order 9066 and the 1944 Supreme Court decision that ruled it “a military necessity” were the inevitable result of a century of anti-Japanese and anti-Asian racism. Written for students ages 12-18, this compelling work should be a “must-read” for adults as well.

Haiku Activities/Asian Arts & Crafts for Creative Kids: Learn to Express Yourself by Writing Poetry in the Japanese Tradition, by Patricia Donegan (2003; ages 7-12).

This useful guide is one work in a series of “how to” children’s books on Asian arts and crafts. Here Patricia Donegan introduces the Japanese poetry known as haiku, offering seven keys to writing it: 1) form; 2) image; 3) kigo (season word); 4) here and now; 5) feeling; 6) surprise; and 7) compassion. She emphasizes the importance of topic, spirit, and characteristic elements over adherence to traditional syllable counts. In addition, this book provides instructions for five haiku projects, including creating haiga, a Japanese art form that combines an image (painting, drawing, or photograph) with a haiku poem.

Temple Alley Summer, written by Sachiko Kashiwaba and illustrated by Miho Satake (2011); translated by Avery Fischer Udagawa (2021; ages 8-13).

I really enjoyed this excellent ghost story/mystery that includes within it a fantasy “story-with-a story” that the main character learns was never finished. Kirkus Reviews praises it as “An instant classic filled with supernatural intrigue and real-world friendship.” The following description is from the novel’s back cover:

"One rainy night, Kazu sees a strange figure in a white kimono sneak out of his house—was he dreaming? Did he see a ghost? The next day at school, the very same person is sitting in his class—and all his friends are convinced that the ghost-girl Akari has been their friend for years. If that isn't weird enough, Kazu learns that his house is in the exact location of an ancient temple called Kimyō, which, legend has it, could bring the dead back to life!

For his summer project, Kazu investigates the forgotten temple’s history, hoping to discover whether rumors of its power are true. He and Akari search for the ending of the unfinished story, which they believe will reveal the temple’s secrets and the ghost-girl’s fate.

The foliage and a mature cone of a hybrid pine tree (Pinus armandii x koraiensis) on the Garden’s northern hillside. (photo: Aleks Monk)

FICTION AND NON-FICTION FOR ADULTS AND MATURE TEENS:

A Beginner’s Guide to Japanese Haiku: Major Works by Japan’s Best Loved Poets, by William Scott Wilson (2022).

This introduction to Japan’s “best loved” haiku poets—Basho, Buson, Issa, and Shiki—also contains haiku by poets whose works are rarely available in English translation, including six women poets and the novelist Natsume Soseki. Compiled by renowned author and translator William Scott Wilson, the book features 26 poets, with introductions to their life and work, and 550 poems, reproduced in the original Japanese as well as in English translation. It also includes new translations by Wilson. A comprehensive introduction to the haiku form, it covers works by Japanese masters from the fifteenth century to the present.

Looking Like the Enemy: My Story of Imprisonment in Japanese-American Internment Camps, by Mary Matsuda Gruenewald (2005).

Mary Matsuda Gruenewald (1925-2021) was born in the U.S. and grew up on Vashon Island, working with her parents and brother on their small strawberry farm. She was 17 years old in 1942, when she and her family were incarcerated at Pinedale Assembly Center, near Fresno, California—the first of a series of prison camps they were moved to before her 1944 release.

Like so many Japanese Americans, she buried her memories for decades and only confronted them at age 70, when she began writing this memoir. It was published 10 years later. The following description is from the book’s website:

“Looking Like the Enemy is told from the heart and mind of a woman now over 80 years old who experienced the challenges and wounds of her internment at a crucial point in her development as a young adult. Gruenewald brings passion and spirit to her story, superbly capturing the emotional and psychological essence of what it was like to grow up in the midst of this profound dislocation and injustice in the United States.”

Gruenewald’s detailed memories of her painful experiences and struggle to retain her dignity and emotional health give this memoir a depth and emotional power that more factual histories often lack. I was moved by her resilience and how she rebuilt her life after incarceration, becoming a health care professional and, later in life, a public speaker and anti-racism activist. It was fascinating to learn of her connection to Seattle. For more than 25 years she worked as a registered nurse at Seattle’s Group Health, becoming Nurse Manager of the ER, and in 1970 she founded the Consulting Nurse Service, which gave members a new benefit—telephone consultations with RNs.

Japanese Garden Notes: A Visual Guide to Elements and Design, by Marc Peter Keane (2017).**

Marc Peter Keane is an American garden designer and author who lived in Kyoto for almost 20 years, designing and building gardens for Japanese clients, before returning to the U.S. The New York Times praises him as "the undisputed American master of Japanese garden scholars.”

The book jacket of Japanese Garden Notes describes his recent designs as blending “traditional Japanese culture with a contemporary understanding of nature.” In addition, it cautions prospective readers that the book does not tell us how to make a “stereotypical” Japanese garden. Rather, it’s “a guide to understanding the myriad aspects of Japanese garden design that make it so compelling.”

On his website, Keane describes the book as his “personal journey through one hundred of Japan’s finest gardens”:

“As Keane walked through each of these gardens, camera in hand, his eye was caught by elements of the garden, anything from large-scale design issues of overall balance to minutiae that only the most practiced eye would notice such as the way bamboo nodes align in a fence. Each of these elements—over 130 in all—has become a theme in this book. To leaf through its pages is to wander through a hundred gardens with a personal guide and to experience their colors, forms and compositions through a designer’s eyes.”

Point Zero, by Seichō Matsumoto (1959); translated by Louise Heal Kawai (2024).

Published in 1959, this fascinating crime novel by Seichō Matsumoto (1909-1992) was translated into English in only recently, in 2024. A prolific author of many fiction and non-fiction works, Matsumoto revolutionized Japanese crime fiction to include social criticism, here the taboo of Japan’s “pan-pan girls,” women who worked as prostitutes catering to GIs during the country’s post-war American occupation.

Foregoing the genre’s conventional plot devices, this early work was a revelation of human psychology and ordinary life—and Matsumoto’s vision that crime and corruption are not limited to criminals but also deeply embedded within the larger society.

Matsumoto’s novel also features a female protagonist, a young woman who investigates the disappearance of her husband after a four-day honeymoon. As described on the publisher’s website, Teiko is “respectful of the proprieties expected of a Japanese woman of the time, but stubborn, intrepid and a naturally intuitive sleuth.” She travels northwest from Tokyo to snowbound Kanazawa, the city where he had been working, and commits herself to uncovering the truth.

Corinne Kennedy is a Garden Guide, frequent contributor to the Seattle Japanese Garden blog, and retired garden designer.