Part One: The World of Wabi-Sabi. "What is Sabi?"

By Yukari Yamano

The Seattle Japanese Garden (Photo by Yukari Yamano)

I have enjoyed the summery weather since May this year. I believe that we have had less rain and more sun compared to last spring. I love the sun. I love the blue sky. I have fully welcomed this cheerful weather that we do not usually have consecutively in the spring, winter nor fall. You Seattleites, on the other hand, may have found yourselves becoming less sharp and more frustrated because of this mellow weather. It is too perfectly cheerful and has no space for your imagination to enjoy any of the melancholic ambiance that comes from gloomy weather. If so, you may be the kind who would understand and enjoy Wabi-Sabi.

Wabi-Sabi is a Japanese aesthetic ideal often considered together with Zen Buddhism. It is composed of two words, Wabi (侘) and Sabi (寂). Sabi is materialistic forms of imperfection and impermanence and Wabi comes from spiritual fullness and positive mindset to embrace the imperfect world of Sabi. I would like to explore the Wabi-Sabi world with you. First Let’s look at Sabi.

The World of Sabi: Fujiwara no Syunzei (Fujiwara no Toshinari)

Sabi encompasses the beauty found in loneliness, imperfection, and impermanence. Originally, it was a term used to describe the hardships and loneliness of life. However, Fujiwara no Shunzei (藤原俊成), also known as Fujiwara no Toshinari (1114 – 1204), a Japanese poet, courtier, and Buddhist monk of the late Heian period, recognized the elegance within lonely and imperfect expressions. He was the father of the renowned waka poet Fujiwara no Teika, who edited numerous waka books, including the famous Ogura Hyakunin Isshu—an anthology of one hundred Japanese waka poems by one hundred poets. The positive significance of sabi was first observed in the Sumiyoshisha Poetry Contest (住吉社歌合) records. Shunzei praised Taira no Tsunemori's poem (平経盛 1124-1185) for its sensitivity to the atmosphere and skillful use of the word sabi (Urasabishikumo) to depict the solitary scene.

住吉の 松吹く風の 音たえて うらさびしくも すめる月かな

Sumiyoshino Matsuhukukazeno Ototaete Urasabishikumo Sumerutsukikana

at Sumiyoshi,

the sound of breeze through pines disappeared

the crisp moon appears in loneliness

― Poem created by Taira no Tsunemori (平経盛 1124-1185) at the Sumiyoshisha Poetry Contest

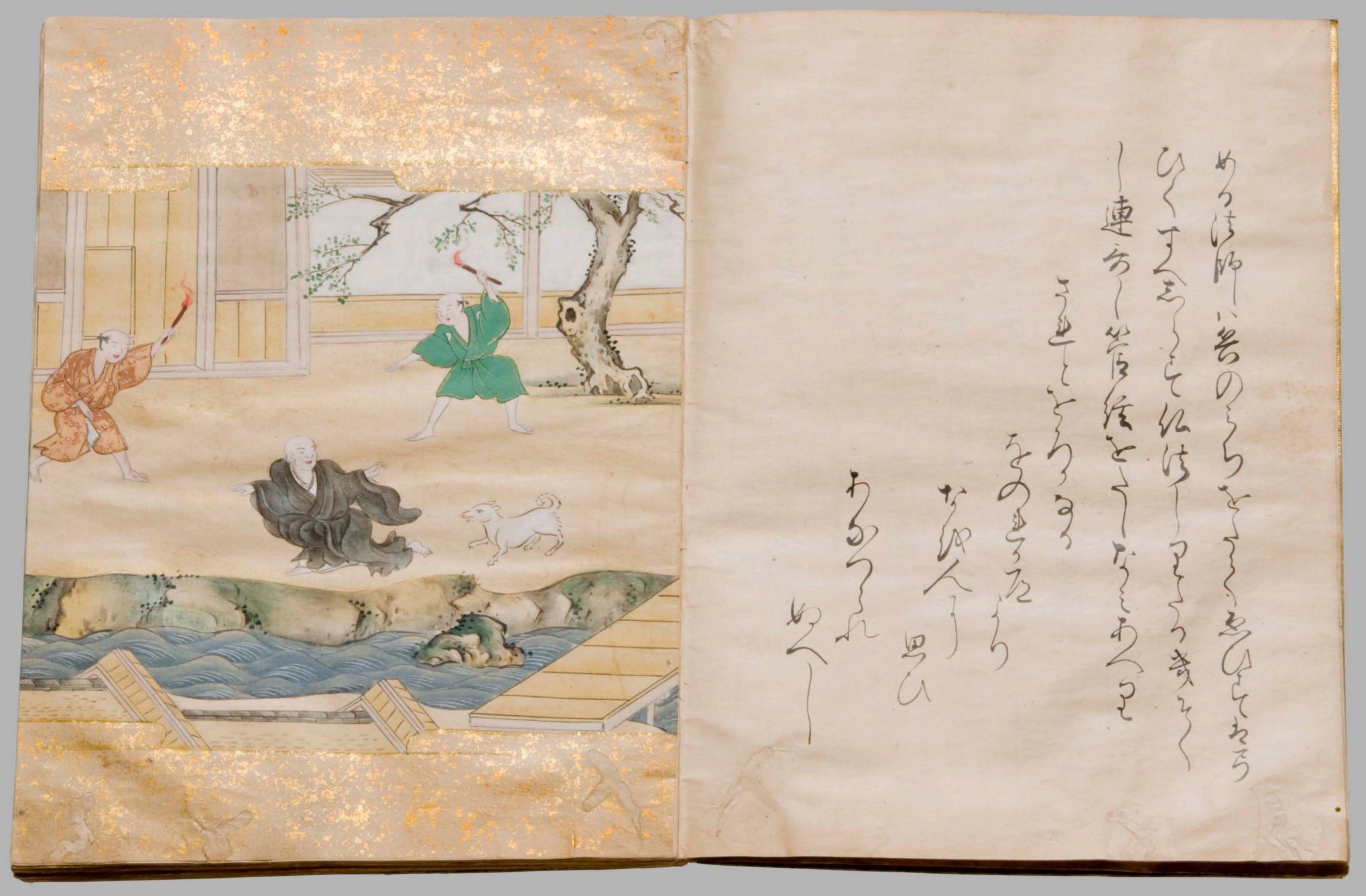

Sample Record of the Sumiyoshisha Poetry Contest — 住吉社歌合 Sumiyoshisha Utaawase (1128) Cultural Heritage Online

The World of Sabi: Yoshida Kenkō

In the late Kamakura period (1192-1333), between 1330 and 1331, Tsurezuregusa (徒然草, Idleness) was written by Yoshida, Kenkō. Tsurezuregusa is one of three very famous essays written in ancient Japan (the other two are: Hōjōki by Kamo no Chomei and Makuranosōshi by Sei Shonagon), and Yoshida Kenkō’s way of viewing the world expressed Sabi aesthetics.

“Are we to look at cherry blossoms only in full bloom, the moon only when it is cloudless? To long for the moon while looking on the rain, to lower the blinds and be unaware of the passing of the spring - these are even more deeply moving. Branches about to blossom or gardens strewn with flowers are worthier of our admiration.”

― Essays in Idleness: The Tsurezuregusa of Yoshida, Kenkō, Translated by Donald Keene

Sample page from Tsurezuregusa (Edo Period) Senshu University Collection

Sabi is a combination of austere elegance and the loneliness around it. Everything on earth decays and becomes old. They get dirty, broken and degraded. This state which is deteriorating is called Sabi and considered as a complex and unique form of beauty.

In the next blog, I would like to talk about Wabi. Stay tuned.

Read more about Wabi-Sabi. Check out “Wabi-Sabi: The Japanese Aesthetic of Impermanence and Simplicity” written by Corinne Kennedy.

Yukari Yamano is an event coordinator at the Seattle Japanese Garden, a native Japanese and a Japanese history buff.